Absurd Names and Archival Erasure: The Paradox of Totalitarianism, circa 1941

May 1, 2024

Aisha Valiulla, T. H. Breen Digital Media Fellow, 2023--24

A brief introduction of the city of Zlín, located in the Carpathian highlands in the southeast of the Czech Republic, might naturally focus on its labor history, as this Atlas Obscura article has done. For one, it was the original headquarters and hometown of the Bata Shoe Company, founded by Tomáš Bat’a in 1894 and now a global international retailer of shoes with branches in over 70 countries, excluding the United States. One could talk about its history as a factory town, the unique box-like architecture of its company homes puncturing the rolling landscape with stark right angles. One could talk about its unique embroilment with the Holocaust; as part of the regions that fell first to Nazi expansion, Zlín and its environs endured one of the longest occupations in World War II. And among the first uses of Jewish slave labor from Auschwitz-Birkenau was at a nearby Bata shoe factory.

Below: Bata Housing in Zlín, Czech Republic.

But we’re going to visit Zlín in early winter, 1941, through an odd little story that Dr. Ben Frommer encountered when working on his upcoming monograph, The Ghetto Without Walls: The Holocaust in the Nazi Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia. The cast of characters? A mysterious stranger with a ludicrous name, a village under siege, and an auction list. The takeaway? A window into the unique psychological stresses of life under brutal occupation, into the surprising realities of absolute power running unchecked in petty ruralities, and what such realities might mean for enterprising historians on the hunt for archives.

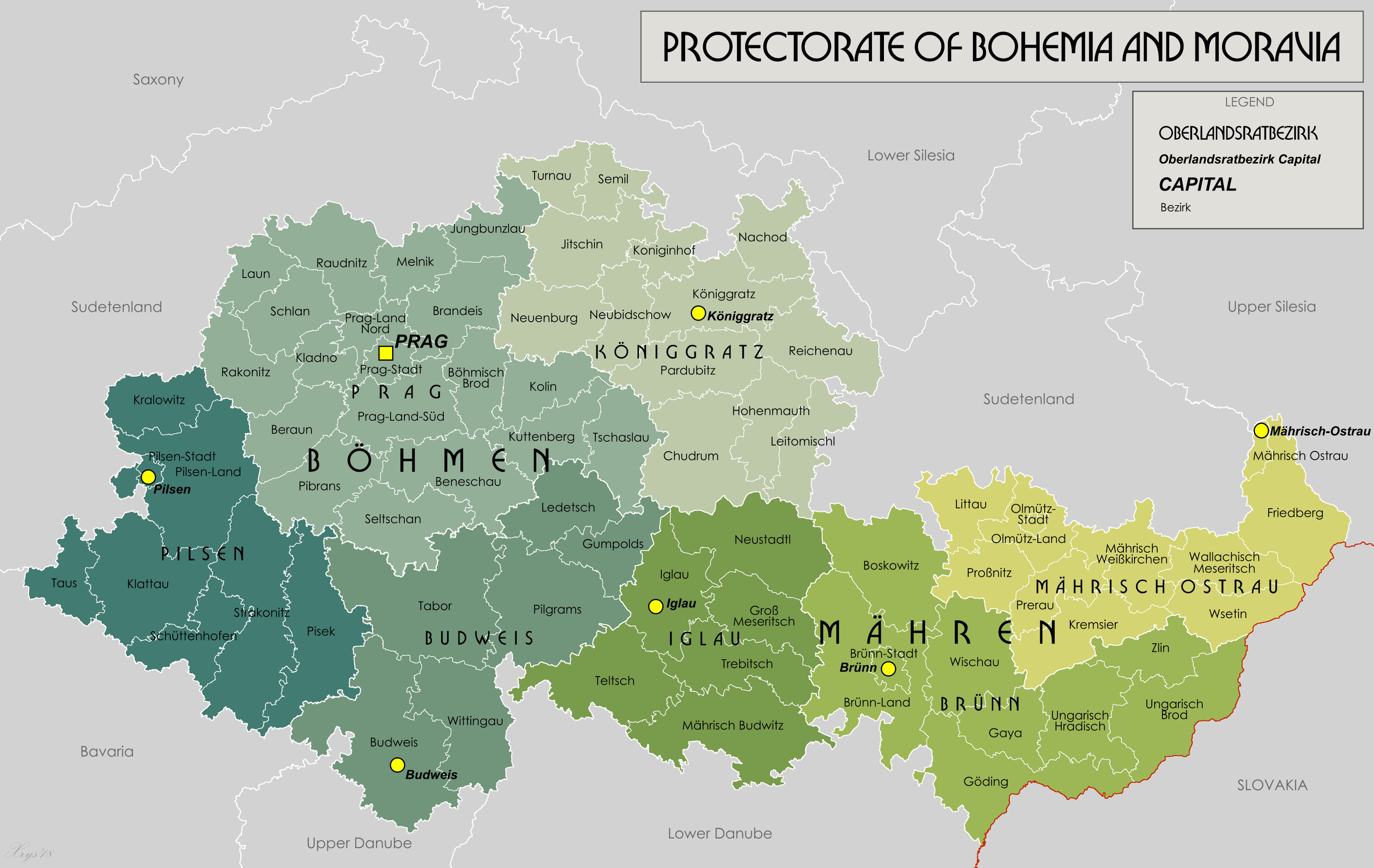

On the last day of January, 1941, a man in a uniform showed up in the village of Malenovice, near Zlín. His name? Margi Wagitasi. His claim? That he was a Gestapo officer sent to oversee the possession and disposition of Jewish property. With a name like that, his German and his uniform (the records do not specify which type) must have been impeccable. Perhaps it was equally likely that the atmosphere of the time—a country under foreign occupation, ethnic, sectarian, and religious divisions transcending fever pitch, deportations and executions being tour du jour, and a continent at open war—made people disinclined to look too closely. The Sudetenland, the border regions of Czechoslovakia populated by a German-speaking majority, had gone to Germany in 1938, and in March 1939, Slovakia declared independence. What remained, specifically the provinces of Bohemia and Moravia, was thereafter taken over by the Germans and renamed the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia. In little more than two years, nearly all the Jews of Czechoslovakia would be deported, whether to occupied Poland, to ghettos, and to concentration camps and killing centers. On that cold January day, asking for proof from a mysterious Gestapo agent was probably the last thing on people’s minds.

Below: A Map of the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia, 1940s (Wikimedia Commons). Zlín is to the southeast, in green:

We do not know how or why he was convincing in his claims. What we do know is that the village jumped to attention. Wagitasi was thrown a fireman’s ball and given his own special table. The mayor personally played the flugelhorn for him; the pub-owner kept him in free beer; the local count sent him wood, the mill sent him flour, and the townspeople gave him a house, all free of charge. The local gendarmes followed his orders as he went around ‘inspecting’ and, naturally, making life difficult for the local Jewish population. It seemed everything was going swimmingly—but with a backdrop such as 1941, nothing can go swimmingly for long.

The pub-owner’s son grew suspicious enough to make the 5-mile trek to the Gestapo office in Zlín, an interesting act in and of itself. As Dr. Frommer puts it, “you don’t just walk into a Gestapo office, because you might not walk out.” The Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia was a territory under hostile occupation. While German sympathizers and native fascists certainly existed, the majority Czech-speaking population was hardly in the Gestapo’s good books, to say nothing of the local Jewish Czech-speaking population. Perhaps, as Dr. Frommer speculates, it was the man’s youth; perhaps it was the fact that the pub-owner’s anxious subservience to an unknown upstart pained his son to witness; perhaps he was one of those sympathizers who had walked into a Gestapo office once before and walked out safely enough to revisit the prospect. Regardless, Wagitasi’s game was most definitely up.

What followed is quite routine. Naturally, the Gestapo had never heard of such a man. Wagitasi was arrested, and was unmasked as Isaac Moritz Schlesinger, a Jewish man from Slovakia (indeed a very literary turn. Were this a fictional story, we’d accuse the author of being far too on-the-nose with his plotting and characterization). The records then fall silent on his fate. The last entry in the archives, dated May 1941, is an exhaustive list of his belongings which are all up for public auction, undersigned by his wife, who also disappears from the historical record. Such an auction was most likely a penalty, which signifies Schlesinger’s conviction and/or death. Whether he died in a concentration camp or in the backyard of the Gestapo office in Zlín is unknown. Neither he nor his wife show up in the deportation lists from 1941, 1942, or even 1943.

Below: War-time era postage stamps (c. 1943), depicting Nazi occupation of Bohemia and Moravia:

In contextualizing Wagitasi’s ill-fated escapade, it is significant that we explore how Dr. Frommer stumbled upon it in the first place. While attending a Fulbright Scholars’ conference held in a wine cellar in eastern Moravia, he thought he might as well visit the regional archives, where he found documents that did not exist in the main archives in Prague. Turns out, those in the center were both under more direct oversight of higher-ups and more in-tune with the political and military winds of the times. Whether under orders or with the foresight of the possibility of post-war trials, Nazis in Prague were more likely to destroy records that they thought were too incriminating to keep. But in some regional archives, such documents remained mostly untouched. For instance, wartime situational reports of the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia barely mentioned the Jews because, as Dr. Frommer found out by visiting one of the regional archives, there was a different set of reports specifically on the Jews that had been destroyed in the central archives. What this meant was a view of daily life in the periphery that was only hinted at from the documentation in the center.

Below: The Zlín State District Archive located in Klečůvka, helpfully labeled ‘Archive’ (Wikimedia Commons):

And what was daily life in the periphery and the ruralities like? In 1941, legislation limiting the civil and daily liberties of Jews was already implemented, such as limited shopping hours, restricted movement; by September of that year, they would be confined to their ‘home communities.’ But, as Dr. Frommer reminds me, being limited to your ‘home community’ of Prague, a city of more than a million people, versus a small village were two very different things, very differently experienced. For a Prague Jew, confinement to city limits did not drastically alter the minutiae of everyday life. For a Jewish family in a village in the provinces, this was a seismic shift. If they were the only Jewish family in the village, it was essential isolation and ghettoization even before they were physically pushed into ghettos. Unable to visit children or relatives in neighboring villages, unable to even attend their funerals (only three mourners were allowed, and since Jews were often allocated burial grounds well outside the village limits, it was in violation of the ‘home community confinement’ rule), rural Jewish families truly experienced a ghetto without walls. In addition, distance from urban centers was also distance from oversight; the provinces were witness to greater cruelty, greater excesses of violence, and, as we saw with Wagitasi’s escapade, greater opportunity for extortion and crime. In Dr. Frommer’s words, “More inventive prohibitions, more corruption, more abuses.” Autonomy from the chain of command meant, unfortunately, a chance for every petty tyrant to indulge in the worst excesses of power.

Herein lies the contradiction of totalitarianism: the more authoritarian the rule, surprisingly, the more chaotic the society underneath. While absolute power running unchecked would imply rigid control of a terrified people, the reality was that because of the sheer terror that such tyranny engenders in a subject population, people actively avoided interaction with the authorities and thus, allowed for miscreants, opportunists, and the like to actively undermine those authorities and replace their supposedly-iron grip on the population. In other words, Dr. Frommer says, “these repressive systems work against themselves.” Who among the subject population in the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia—the Czech-speakers and even more so the Jews—would dare report to the Gestapo and bring the attention of the wolves onto themselves? Far better to pay that extortive sum of money, to give that sack of flour, to endure the abuses, and survive for another day. Indeed, Dr. Frommer told me, he discovered dozens of similar examples of malevolent opportunism in the archives, to say nothing of the likely hundreds, if not thousands, of such cases that went unreported and uninvestigated. Some claimed to be Gestapo, or have friends in the Gestapo, or claimed to be faking to be Gestapo (especially during the post-war trials), or threatened to turn the victims in to the Gestapo. They extorted money, food, shelter, and of course, sexual favors. The archives can only bear echoes of the pain that people generally, and women especially, suffered and endured in an unforgiving vortex of silence and cold pragmatism.

Below: Hitler’s sole visit to Prague, inspecting troops in the courtyard of Prague Castle (Wikimedia Commons):

It is rather elegant that the first entry on this blog, Dr. Brack’s charlatan, and this one, near the end of the year, share such similar points: false claimants under false names, showing up in distant provincial settings where such hoodwinks are easier carried out. But the two differ in one aspect: whereas the Mamluk imposter was immediately regarded with suspicion, the Nazi imposter had the entire village dancing on his whims. Margi Wagitasi’s exploit, one of the more audacious among untold thousands, reminds us of the psychological stress and terror of life under Nazi occupation, even in the early days of World War II. That such a man, showing up with almost nothing to back up his claims and indeed a pseudonym that works against him (if he was claiming to be a German Gestapo officer, shouldn’t he have gone for stolidly safe Germanic name like Hans? Or Rolf?), was so indulged by the villagers speaks volumes to the fear, apprehension, and uncertainty they felt. A mere two years earlier, had the Nazis not entered the picture, Wagitasi would have been swiftly and immediately recognized for the charlatan he was and unceremoniously chucked out on his butt. In 1941, however, matters—and consequences—were much more urgent.

Dr. Frommer’s research and upcoming book is a sobering and timely reminder of the various contingent factors that constitute archival erasures. The tensions between center and periphery, metropole and colony, are hardly groundbreaking, but even in territories as small as the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia, under oppression that seems all-encompassing in its totality and brutality, Wagitasi’s story illuminates the range of trauma, stress, and fear that varied from place to place. Jewish life under Nazi occupation was horrific in every instance, but provincial and isolated settings added greater complexity and potential for abuse. Despite its absurdity, Wagitasi’s tale is not amusing—but then, when discussing genocide, tyranny, dispossession of home, livelihood, and life, is anything?