Climate, Soil, and an 800-Year-Old Mystery: Geoarchaeology and New Frontiers of Urban History

April 1, 2024

Aisha Valiulla, T. H. Breen Digital Media Fellow, 2023--24

The first postdoctoral fellow of the new Material Archaeology Lab in Harris Hall is Dr. Bongumenzi Sithembiso Nxumalo of the University of Pretoria, South Africa. While discussing his work at the lab—and indulging my curiosity at the new function of our old Seminar Room (the walls yet remain yellow, people!)—Dr. Nxumalo told me a fascinating story that not only revisits and problematizes existing historical narratives, but also opens new frontiers of geoarchaeological methodology. In doing so, his work is a reminder of the sheer breadth and scope of urban history in Africa.

Some 300 miles north of Johannesburg, awash in dazzling sunlight lies Mapungubwe (c. 900—1300 CE), once the capital city of an eponymous kingdom in southern Africa. Meaning ‘hill of the jackal,’ the site is now a World Heritage Site, the heart of the Mapungubwe National Park and was, in Dr. Nxumalo’s own words, “the cradle of urbanism” in southern Africa. Located on the agricultural floodplains, Mapungubwe abuts the confluence of two rivers—the Shashe, flowing south from Botswana and Zimbabwe, and the Limpopo, flowing eastward from South Africa. By the thirteenth century, it was the center of a sophisticated pre-colonial state that traded gold and ivory with China, the Indian Ocean world, and Egypt. Its people herded cattle, sheep, and goats and cultivated sorghum and millets. Around the mid-thirteenth century, however, Mapungubwe began to decline, ostensibly due to effects of climate changes linked to the Little Ice Age (1250—c. 1850 CE). The climatic changes in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries apparently led to such excessive flooding and erratic rainfall patterns as to make the Shashe-Limpopo basin ecologically non-viable. Consequently, the site was abandoned in favor of Great Zimbabwe, a city about 185 miles to the northeast, which began to gain prominence around the fourteenth century—or so the story goes.

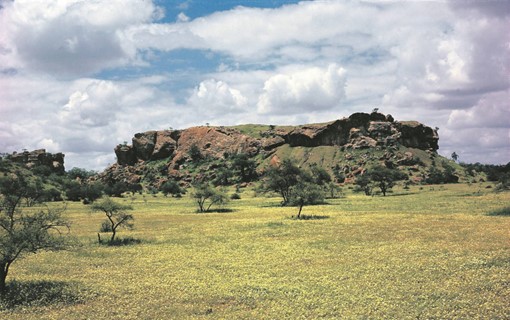

Below: Mapungubwe Hill and Archaeological Site

Both Mapungubwe and Great Zimbabwe are tremendously important: as Dr. Nxumalo puts it, they “provide the earliest evidence for class distinction and sacral leadership” in southern Africa. In investigating these early state formations, however, he discovered a few anomalies that problematized the linear evolution of Mapungubwe against the backdrop of the climatic hypothesis in the Shashe-Limpopo Basin. First, a mere two miles away from Mapungubwe lies the site of Samaria 4-1, part of the Mapungubwe state, which, surprisingly, has evidence of continued human occupation and landscape cultivation during and after the time of Mapungubwe’s supposed collapse. If the landscape had become so hostile as to necessitate the abandonment of a thriving metropolis such as Mapungubwe, then why did people continue living and re-working the Samaria floodplain, but a stone’s throw away? Second, the climate hypothesis of Mapungubwe’s abandonment is too simplistic, for it superimposes climatic effects (based on historical/oral sources) of the Little Ice Age observed in the northern hemisphere to places, geographies, and climates that are far removed from it. In other words, climatic studies of the medieval period in southern Africa have not been undertaken in significant enough ways (i.e. lacking empirical paleoenvironmental data) to safely argue that the changes brought by the Little Ice Age affected both the Northern and Southern hemisphere in similar ways.

Below: Map showing archaeological sites in Mapungubwe National Park and the green rectangle in the South Africa map highlights the Shashe-Limpopo Basin (Nxumalo 2019).

Moreover, several studies have shown that global climatic changes had varied impacts in local landscape contexts, especially one as complex as the Shashe-Limpopo confluence. Not only are hydrological changes in the Shashe-Limpopo basin “highly influenced by seasonal variability and distribution of rainfall,” it is also a seismically active area. Even today, though the region looks dry and arid, it supports farming on an industrial scale: ZZ2, the largest producer of tomatoes in South Africa, is centered around 4.5 miles northwest of the Mapungubwe site.

Historical scholarship on Mapungubwe, more interested in navigation, Indian Ocean trade, and ethnographic records, and language evolution, has overlooked the climatic hypothesis. Mapungubwe’s climate history existed solely in oral histories, which married sacred leadership to tenuous climate data and the consequent abandonment of the state. According to one version of the story, the gods/ancestors expressed their displeasure with the city’s rulers and manifested their anger with excessive flooding and ecological devastation; consequently, an overthrow of the ruling class and abandonment of the site occurred. But what then do we do with Samaria 4-1? Not only was it part of the same state society, but it existed on the same floodplain within the Shashe-Limpopo basin. Floods so torrential as to cripple Mapungubwe could not have spared its sister site a mere mile away. To understand the impact of floods across both archaeological sites and for hard data on the climatic sequences of Mapungubwe, Dr. Nxumalo turned to geoarchaeology.

Below: The golden rhinoceros of Mapungubwe, one of many artifacts found at the site.

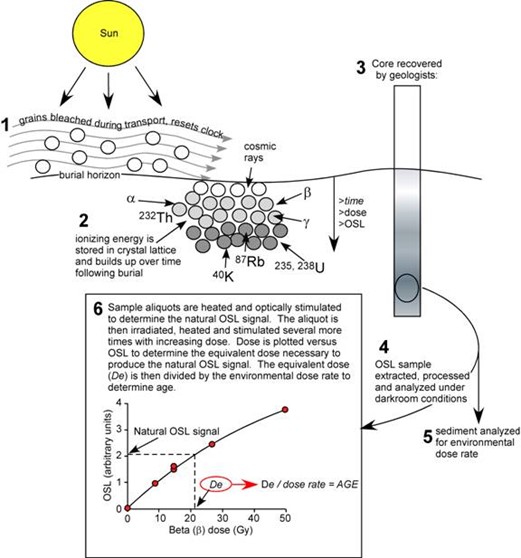

Geoarchaeology is a geo-scientific approach that utilizes earth scientific techniques, such as soil macro-micromorphology, computational modelling, geochemistry, electrochemistry (such as reduction-oxidation potential), pH analysis, and Optically-Stimulated Luminescence (OSL) dating, to answer archaeological questions and contextualize human and environmental changes. Using hydrological modelling in geographic information systems, hydrologic engineering river analysis systems and soil analysis, Dr. Nxumalo tested the hypothesis of climate variability by focusing on rainfall patterns and simulating their impacts on landscapes to understand how excessive flooding may have contributed to the decline of Mapungubwe. He conducted geoarchaeological surveys at both the Mapungubwe site and the nearby, much less known (and thus much less disturbed) Samaria 4-1 site, studying evidence of excessive rainfall and flooding. A high accumulation of manganese in a substratum of soil, for instance, usually indicates changing water tables, while a layer of alluvial deposits (loose granular rocks in the sediment) indicates abrupt deposition by flooding. Sedimentary evidence is then dated using OSL, which estimates the time when a given soil sample was buried or hindered from light/heat exposure or sunlight. In other words, not only do these techniques allow us to approximate flooding episodes centuries ago, but they also aid contextual interpretation such as the timing of sediment build-up to know when events took place.

Below: a diagram detailing how OSL-dating works

And what context did the earth provide for the history of Mapungubwe? Dr. Nxumalo’s findings, which remain under embargo at Cambridge University, make two main interventions. First, geoarchaeological data does not support the 13th century abandonment thesis. During the period of the so-called collapse of Mapungubwe, there is evidence of human occupation and traces of their anthropogenic footprints such as the presence of ashy and charcoal deposits which were tilled into the earth to heighten soil fertility. At the same time we are told that the landscape had become too hostile for continued human inhabitation, the soil was actively being cultivated for crop growth. In fact, as Dr. Nxumalo writes, “from about AD 1290 to 1697, the Shashe-Limpopo Basin was occupied by early farming communities.” Second, hydrological modelling and soil macro-micromorphology yielded evidence of flooding during the Little Ice Age period, but these flooding episodes were confined to the river reaches and the intensity was attenuated by the river valley vegetation. Apparently, the Little Ice Age did not cause such torrential flooding and hydrological chaos as to lead to the abandonment of the city.

To be sure, that the city was abandoned at some point is a fact. And certainly, landscapes and climates play significant roles in the lifespan of urban settlements. But what Dr. Nxumalo unravels has important implications for the past, present, and future. For Mapungubwe, southern Africa’s earliest state-society, his work is a caution against overly simplistic narratives and an invitation to revisit the reasons for the city’s ‘rise and fall,’ so to speak—to read more carefully into what the landscape itself can tell us. For those times and places in the past where the written record fails us and the oral record provides only shadowy, flickering glimpses, geoarchaeology can fill in the silences with data. Evocatively enough, where voices fall short, the earth itself steps in to tell the story. For the future, earth scientific software technology and techniques pave the way for sustainability and preparation in the face of current climate change. Rainfall simulation modeling, for instance, allows public policymakers to see future spaces for concern and conservation and build/redirect infrastructure to account for such possibilities, while properties and behavior of soil (another thing that Dr. Nxumalo researches) can help predict—and preempt—possible flood zones.

And lastly, for the present, such methodologies highlight the importance of interdisciplinary collaboration, not just within the humanities, but also with the hard sciences such as chemistry, biology, and geology. To be fair, the lines between archaeology and history are blurry enough already, but in the face of petty and myopic qualms such as ‘but is this really history?’, Dr. Nxumalo’s methods and conclusions remind us that everything is history, and everything has history, including the very soil itself. In that vein, OSL-dating provides a particularly evocative image: rocks and fragments buried deep within the earth, holding within their very particles the stories of their formation, their movement, and their burials, embers glowing faintly with the memory of equally dazzling sunlight from centuries ago.

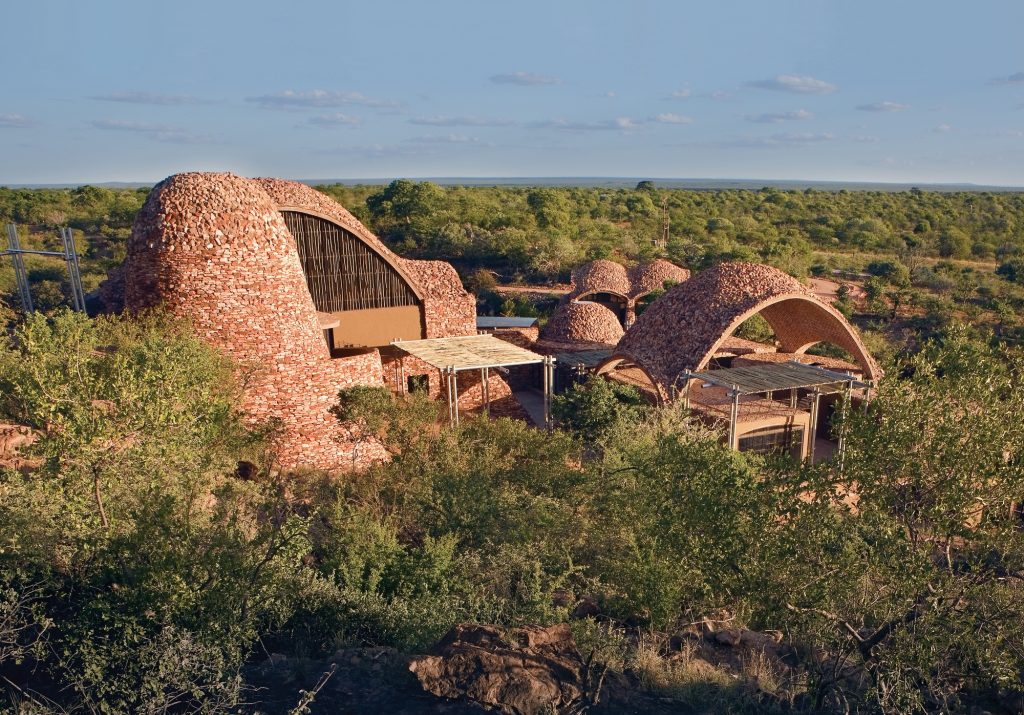

Below: Mapungubwe Interpretation Centre, Mapungubwe National Park, Peter Rich Architects, c. 2009: