One Night in Paris: Gothic Tropes and the Early Modern Cloister

June 1, 2024

Aisha Valiulla, 2023—24 T. H. Breen Digital Media Fellow

Special thanks to Agustín Bayer for help with French translations

Note: This is my last blogpost. My heartfelt thanks to Elzbieta and Ben for allowing me to shape this as I wished, to all those generous enough to give me their time and their stories, and to all of you who took time to read my posts.

For most people, the term ‘Gothic’ conjures up its architectural manifestation: tall spires, vaulted arches, flying buttresses, and solemn cathedrals. Here, Gothic refers to the literary genre and its attendant aesthetics: a looming castle/abbey/vertically-gifted edifice of some sort; a wealthy maiden, usually in distress; a young man, often trying to alleviate her distress; a lecherous villain, ostensibly after the maiden’s fortune or the maiden herself; and the supernatural, be it ghosts, Christian spirituality, or some sort of divinity becoming a tangible force in the world of the story. As a literary genre, the Gothic began with Horace Walpole’s The Castle of Otranto (1764); by the 1790s, Gothic literature had become a best-selling genre, yielding a few giants of the field, such as Ann Radcliffe (d. 1823), whose Gothic novels were continent-wide bestsellers. By 1818, the genre had become so popular—and perhaps, its tropes so tired—that Jane Austen parodied it in her satire, Northanger Abbey, in which the young and innocent Catherine Morland is so obsessed with Gothic novels—the drama! The titillation! The desire!—that she fancies herself living in one when she’s invited to the eponymous abbey after a successful social season in Bath, England.

Below: An example of Gothic literary aesthetics—Sebastian Pether, “Moonlit River Landscape” (1823):

I bring this up because the story that our own Dr. Haley Bowen told me could have come straight out of a Gothic novel. It has all the trappings: a young heiress, a villainous young man, a sufficiently vertically-gifted edifice (a Parisian convent, no less!), and enough drama to justify its preservation in the archives long after the convent was dissolved. The story reveals the novel functions that convents fulfilled in the early modern period, the useful fiction of their impenetrability, and the surprising relativity of freedom itself.

I bring this up because the story that our own Dr. Haley Bowen told me could have come straight out of a Gothic novel. It has all the trappings: a young heiress, a villainous young man, a sufficiently vertically-gifted edifice (a Parisian convent, no less!), and enough drama to justify its preservation in the archives long after the convent was dissolved. The story reveals the novel functions that convents fulfilled in the early modern period, the useful fiction of their impenetrability, and the surprising relativity of freedom itself.

Once upon a time, there lived in Normandy a wealthy young woman called Mademoiselle de la Croix. Heiress to the enormous sum of 27,000 livres (roughly $420,000 today) a year, the chief question of her young life, of course, was whom she would marry. Her parents were divided: the mother’s choice was the first president of the Chamber of Accounts in Rouen, a sufficiently high-status and respectable position in a provincial town, while the father’s choice was Monsieur de Charmois, the son of a noble family in Normandy with ties to the House of Orléans, which, during the Fronde Civil War (1648—53) would come out in opposition to King Louis XIV (d. 1715). Perhaps because of such politics, perhaps for other reasons, M.lle de la Croix’s mother was so opposed to the match that she had her husband legally declared mentally incompetent, which removed him from his patriarchal authority over the household, the children, and all property. This was an astonishing feat in and of itself, but as we shall see, it was not enough. With his ally thus incapacitated, young de Charmois took matters in his own hands and kidnapped 17-year-old M.lle de la Croix, bringing her to the house of another noble family outside of Paris to persuade her to marry him. As the son of a relatively minor noble house, her fortune would have been the making of his. She remained steadfast in her refusal and was soon recovered by her family, who then placed her for her own safety in the Filles-Dieu, a convent located on the famed Rue St. Denis in the heart of Paris.

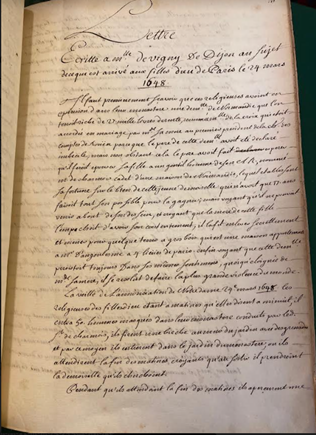

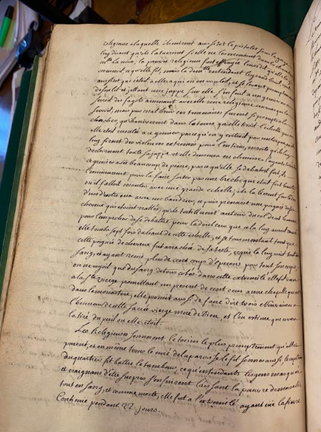

Below: The letter recounting this story, the principal record of the event (courtesy Dr. Bowen):

Founded in the 13th century as a maison de charité to house repentant prostitutes, the Filles-Dieu transformed into one of the most prominent and prestigious religious houses in Paris over the course of the late medieval and early modern period. By the 17th century, which is when our story takes place, it had come to house daughters of the nobility and, having shed its association with prostitutes, enjoyed an affiliation with the famous and politically-connected Fontevraud Abbey of Plantagenet fame. The Filles-Dieu was not alone in such a transformation. The early period of the Catholic Reformation (1545—1648) in the mid-to-late 16th century had seen significant donations to Catholic institutions, but by the mid-1600s these had dwindled, while royal censure against such massive tax-exempt institutions had heightened. In search of new avenues of financial sustenance, convents had begun accepting laywomen into the cloister. These pensioners could be young women sent to convents to be educated and brought up, perhaps amongst female relatives who’d taken religious vows, or older women who ‘retired’ there, so to speak, or women escaping domestic violence without dishonoring themselves in the eyes of society, or even women incarcerated in convents by their husbands. As we shall see, this new intrusion of the laity into the cloister brought with it new entanglements and complexities for institutions that were, at least on paper, meant to be immune and disentangled from the world and civil society.

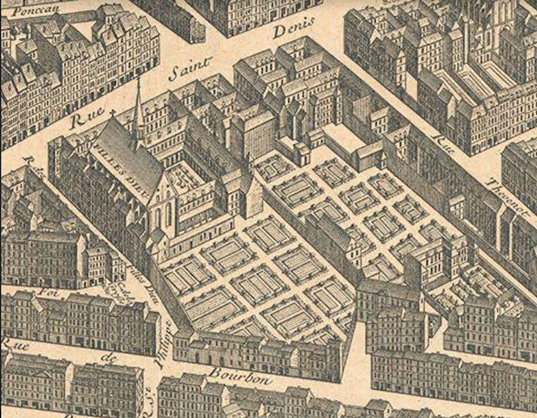

Below: A map of the Filles-Dieu from Michel-Étienne Turgot's map of Paris, c. 1739 (courtesy Dr. Bowen). Note the enormous gardens!

M.lle de la Croix certainly was not disentangled, as much as she might have wished to be so. It was past midnight on March 24, 1648, and most of the nuns of the Filles-Dieu were at midnight matins in the convent chapel. M.lle de la Croix was in bed, attended by her converse sister, a woman assigned to her service and care, when at the wall of the convent arrived Monsieur de Charmois with some 50 young men, all masked. Armed with grenades, they blasted a hole in the wall of the cloister and broke into the convent gardens. They seized a nun who happened to be in the gardens, put a pistol to her throat, and demanded to know the whereabouts of M.lle de la Croix. Meanwhile, the heiress had heard the commotion and deducing correctly that it was for her, quickly put on a skirt over her night chemise and along with her attendant, ran to an attic to hide. She is described as literally pulling up the ladder behind her when the men burst in and dragged her down with such violence that her skirt “was all destroyed” and she was only in her long chemise, a position which to her would have been deeply vulnerable and humiliating. The men managed to bring her to the hole in the convent wall, hoping to take her out over the rubble and then, presumably, force her marriage to de Charmois.

Not one to go gentle into that good night, M.lle de la Croix fought so hard that they tied her to the back of one of the young men and to further immobilize her, wrapped her long hair around his neck. Nonetheless, her struggles continued such that she and her tied captor fell down a remarkable seven times from the ladder, receiving kicks from the men’s spurs all the while; sometime during the horror, her hair were ripped out of her scalp and her head was covered in blood. By this time, the alarm was well and truly raised: the nuns and the parish priest were ringing the bells and the local militia had already come running, to say nothing of a gathering crowd at the site of the explosion. Frightened, the masked assailants fled, leaving the valiant, battered young woman “comme morte,” as if dead, in the gardens. Later, she would reveal that while being taken up the ladder, she had prayed to the Virgin Mary, pledging 100 écus (gold coins) and masses said in her name, and that it was to the Virgin’s intercession that she owed her salvation.

Below: gold écu, struck during the reign of Louis XIII, c. 1641:

Equal to the ferocity of the young woman’s resistance was the justice that was enacted by the state against the perpetrators. De Charmois was sentenced to be broken apart on a wheel before the convent gates, a painful execution method that was rarely sentenced to nobility except in cases of high treason; while we do not know whether he was actually executed in that manner—nobility having “all sorts of ways of getting out of such sentences,” Dr. Bowen tells me—we do know that he was excommunicated, his home razed, the woods of his property cut down as a public display of his dishonor (much like the hair of a woman would be shorn in her disgrace), and 40,000 livres from his property paid to the Filles-Dieu in restitution for its violation. The 50 masked young men escaped identification and thus their punishments, but they were hung in effigy in the town square. The wall where the men had broken in was rebuilt, but with the addition of a marble plaque that named de Charmois, his crime, and his punishment. Under the plaque, they established a cloaque, a cesspit or hole for refuse, where the townspeople would dump their household garbage, both organic and inorganic, at the name of de Charmois and at the wickedness of his transgression. Who he was and what he had done would be stained in perpetuity with literal stinking shit.

Equal to the ferocity of the young woman’s resistance was the justice that was enacted by the state against the perpetrators. De Charmois was sentenced to be broken apart on a wheel before the convent gates, a painful execution method that was rarely sentenced to nobility except in cases of high treason; while we do not know whether he was actually executed in that manner—nobility having “all sorts of ways of getting out of such sentences,” Dr. Bowen tells me—we do know that he was excommunicated, his home razed, the woods of his property cut down as a public display of his dishonor (much like the hair of a woman would be shorn in her disgrace), and 40,000 livres from his property paid to the Filles-Dieu in restitution for its violation. The 50 masked young men escaped identification and thus their punishments, but they were hung in effigy in the town square. The wall where the men had broken in was rebuilt, but with the addition of a marble plaque that named de Charmois, his crime, and his punishment. Under the plaque, they established a cloaque, a cesspit or hole for refuse, where the townspeople would dump their household garbage, both organic and inorganic, at the name of de Charmois and at the wickedness of his transgression. Who he was and what he had done would be stained in perpetuity with literal stinking shit.

The breadth and severity of the state’s punishment behooves us to question why this episode—a horrific one, to be sure, but an abortive attempt with no permanent harm done—garnered such a reaction. And here, the unique role that 17th century convents played in French society deserves careful consideration. Early modern France was a Catholic state and divorce, though not unheard of, was extremely rare. The dissolution of a marriage was a long and convoluted process and legal recourse did not exist for marital rape, domestic violence, or other such marital dysfunction. As sites of sanctuary and refuge for laywomen to escape their households and yet retain their honor, convents in the early modern period became safety valves for the rigid constraints of Catholic matrimony. While this was a welcome and necessary development, the issue was that with convents stop-gapping the inadequacies of the marital institution, there was less pressure on the state to use legislation to address them. Paramount to its new role in civil society was the inviolate nature of the cloister: as a space where the woman could go or be kept without threat to her honor, it necessarily had to be a space devoid of male presence. Consequently, it was in the best interests of both the state and society to preserve convents as sites of honorable refuge and thus, the idea of the cloister as inviolable and sacrosanct. And if one were to blow this ideology wide apart (as de Charmois and his accomplices did via literal hand-grenades) and reveal the fiction of the cloister’s sanctity, the physical threat to women was paralleled by the symbolic threat to the institution of cloisters, of marriage, and in some ways, to the authority of the Church and the French state itself. Small wonder, then, that the state chose to restore the mirage of impenetrability through such swift, thorough, and vicious retribution.

The curious incident of the villain in the night-time also exemplifies the contradictions that the presence of laywomen caused within convent communities. Dr. Bowen tells me she has innumerable examples of women escaping to convents to seek refuge from abusive husbands; some even requested judges to issue orders for their own incarceration in a cloister, simply to enact an additional legal obstacle between them and their husbands who might seek to retrieve them. Therein lay the first contradiction: in providing refuge from marital issues, these cloisters often were drawn intimately into marital issues. Convents that were meant to be removed from domestic dysfunction were, in the early modern period, literally having it played out in their parlors. Angry husbands would come to meet their wives and though they were separated by an iron grate and chaperoned by a nun, men would reach through the bars, attempting to hit their wives, seize their hair, or scream at them. Attendant nuns sometimes testified in marriage dissolution cases, speaking of the runaway wife’s good character and chastity, sometimes testifying to the ways her husband had hurled abuse at her even within the cloister walls. And in so doing, their actions lay bare for us the second contradiction: while the rules of nunnery discourage earthly affections (all the better to remember God, my dear), the reality was a community that had strong emotional ties to each other within the convent and to laywomen outside of the convent, even as the inclusion of those women brought violence to the nuns as well.

Below: 16th century French nuns (Wikimedia Commons):

The literary genre of Gothic hinges on the helplessness of a young woman set adrift (usually without familial and/or male protection) in a dangerous world. Looming edifices and lecherous men are but tangible manifestations of the ever-present, intangible institution of patriarchy and male legal, social, cultural, and religious domination that literally and metaphorically tower over the heroine’s very existence. As Mademoiselle de la Croix’s story reminds us, these Gothic tropes were but literary encapsulations of the patriarchal social reality of early modern Europe. It is deliciously ironic, then, that cloisters—fully enclosed, austere institutions defined by their inhibitions and constraints—become spaces of freedom from that social reality. Dr. Bowen told me of a woman who, held in a villa by her husband’s soldiers against her will, literally dug a tunnel to the gardens of the convent next door, in her own words “de trouver mon liberté.” To find my freedom. She essentially popped up like a gopher in the gardens, exchanging one building she couldn’t leave where she was a prisoner for another building she couldn’t leave where she was free. As Dr. Bowen concluded in our interview, freedom is relative and not necessarily correlative to freedom of movement. Equally important, perhaps even more for this woman, would have been the freedom of choice and freedom from oversight. While M.lle de la Croix’s story cautions us not to overstate the refuge that convents could offer, it does exemplify the novel and contradictory roles of cloisters in the 17th century and in so doing, asks us to reflect on our perception of monastic institutions, of their inviolability, and indeed of liberté itself.

Below: an allegorical rendering of a woman finding her freedom: